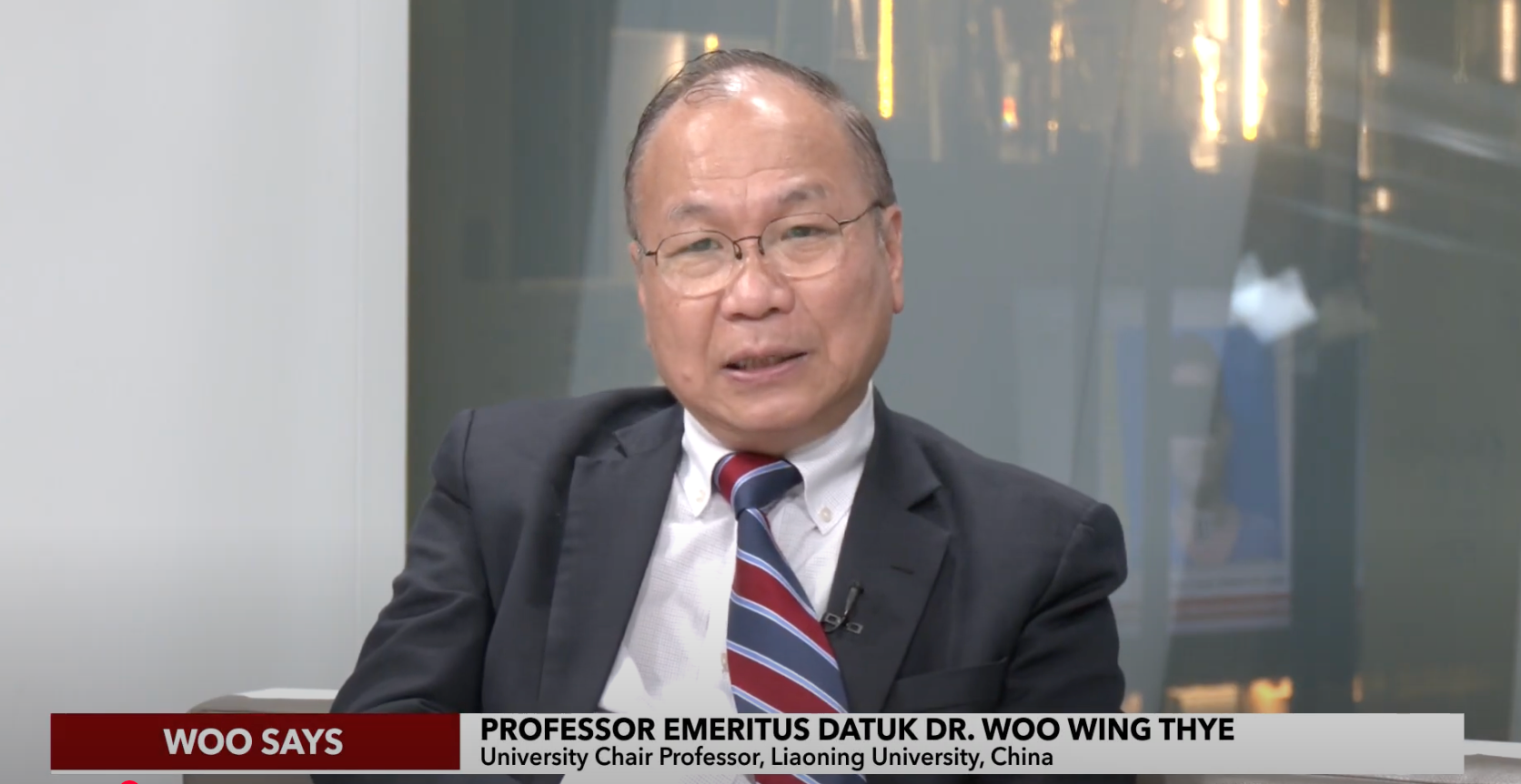

Awani International, the global affairs division of Malaysia’s leading news network Astro Awani, continues its signature series Woo.Says, a weekly dialogue between Professor Wing Thye Woo (University Chair Professor at Liaoning University and Distinguished Professor Emeritus at UC Davis) and Ms. Melisa Idris (Senior News Editor at Awani International).

In the third episode, “Is ASEAN Just a Glorified Talk Shop?”, Professor Woo examines whether ASEAN can maintain its strategic autonomy amid intensifying U.S.-China rivalry. Drawing on recent developments at the ASEAN Summit, he argues that while ASEAN’s consensus-based model may seem slow, it is quietly building resilience, deepening cooperation, and carving space for regional agency in a polarised world.

Melisa Idris:This week, the world turns its eyes to Southeast Asia as the ASEAN Summit is underway. Leaders are gathered, communiqués are being drafted, and the traditional cross-body handshakes are being photographed. In a world increasingly shaped by the tug-of-war between the U.S. and China, the question we're asking is: What does this moment mean for ASEAN? Is ASEAN just a glorified talk shop? It has been criticised for being long on meetings but short on muscle. What’s your take?

Prof. Woo: I would say that ASEAN is less of a talk shop than it was before. Let's start with why people perceive it as such. One key reason is the way ASEAN is structured, decision-making is by consensus. That means nothing is adopted under the ASEAN name unless everyone agrees.

Getting consensus from a diverse group of countries is difficult. So yes, it may appear as though ASEAN was designed not to act decisively. But that’s not quite fair. Some have criticized ASEAN as a hypocritical talk shop: pronouncements are made with no intention of follow-through. But there's also another type of talk shop, a constrained talk shop. That is, ASEAN has the will to act but not the ability to do so.

Melisa Idris: So it's not just talk, but ASEAN’s options are constrained. Can you give an example of how ASEAN is becoming more action-oriented?

Prof. Woo: Yes. Take this current summit. ASEAN has given the ASEAN Centre for Energy a mandate to draw up a plan for the ASEAN Power Grid. That’s an initiative to connect the region’s national electricity systems, essential for achieving net zero emissions.

Melisa Idris: That's interesting. When did you start seeing ASEAN becoming more than a talk shop?

Prof. Woo: The progress began when ASEAN moved beyond bilateralism and started to think regionally. That shift was driven by growing internal cohesion. Countries realised that being an ASEAN member caused no harm and that ASEAN institutions could not go rogue or pursue the private agendas of a subset of members. The Consensus principle of decision-making built trust in ASEAN institutions as regional mechanisms.

Some problems cannot be solved alone. Take transboundary haze pollution, haze from land clearing in one country causes health issues in another. That’s a classic example where a regional approach is essential. ASEAN’s slow, consensual model helped build familiarity and confidence in ASEAN as a regional organization. Over time, that enabled more cooperation, like the ASEAN Free Trade Area.

Melisa Idris: In the face of ongoing U.S.-China tensions and a global landscape that seems increasingly “polarized”, how can ASEAN maintain its relevance and strategic autonomy?

Prof. Woo: ASEAN must do two things. First, we must offer constructive ideas to both superpowers, proposals to reduce mutual suspicion and to identify pathways to workable compromises. Second, ASEAN must be able to build timely coalitions, that are small, nimble, and united, to safeguard its desire for neutrality through collective engagement.

These coalitions should not be too large to manage but big enough in terms of population and GDP to achieve weight in bargaining. That means working with countries like Korea and Japan and ideally, the European Europe. The European Union has both population and economic clout and, like us, has been adversely affected by current global tensions.

Melisa Idris: That sounds like what you mentioned in a previous episode, a caucus of “buffer states”, right?

Prof. Woo: Exactly. Rather than always striving for one-size-fits-all global solutions, ASEAN can work with like-minded middle powers, countries with ties to both the U.S. and China, and a shared interest in maintaining global stability.

We already have strong people-to-people ties with Korea, Japan, and Europe. These are countries where ASEAN members send students, do business, and have historical linkages. This shared experience and mutual respect make collaboration easier.

Melisa Idris: So are we on a practical path forward?

Prof. Woo: Yes. Consider how ASEAN has evolved over the decades, from a platform for dialogue to one forming coalitions that enhance economic prosperity. This year’s ASEAN Summit includes a meeting with the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC).

The GCC countries have significant capital they’re looking to invest, and ASEAN, especially countries like Malaysia, offers attractive, stable opportunities. At the same time, the GCC maintains very close ties with the U.S., which helps ASEAN balance its relations.

So by showing that it is possible for ASEAN to be friendly to all sides, ASEAN will be able to continue multilateral economic engagements based on the on the age-old principle of comparative advantage, whereby the division of labour across countries raises productivity everywhere and benefits everyone.

(The views do not necessarily reflect those of the publication. For access to the original link, please contact us: international@lnu.edu.cn.)